Most writing coaches agree that the first 1/4 of your story is where you reveal your characters and show their world while introducing hints of trouble and foreshadowing the first plot point. That is the first act, so to speak. The Calamity: Something large and dramatic must occur right around the 1/4 mark to force the hero into action, an intense, powerful scene that changes everything. Quite often the inciting scene will be comparatively disastrous, and one that that forces the protagonist to react. He/she may be thrust into a situation that radically changes their life and forces them to make a series of difficult decisions. Putting this together requires intention on your part:

The Villain: Conflict drives the story. We know a great story has a compelling protagonist, but if you want to have a conflict that will impact the reader, you must have a worthy adversary. The hero has an objective, and so does the villain. You must identify the opponent. Who are they and what is their power-base?

We are rarely perceived as being villains for no reason. We don’t realize we are arrogant or obstructive—we have goals and don’t understand why others can’t see that. You must identify why they are so committed to thwarting your heroine.

Do the hero and the villain know each other, or are they faceless enemies to each other? How does the adversary counter the hero’s efforts? In fantasy, and often in thrillers and horror, we have an adversary who is capable of great evil. They may have supernatural powers, and at first they seem invincible. Their position of greater power forces the hero to become stronger, craftier, to develop ways to beat the adversary at his game. A strong, compelling villain creates interest and drives the conflict. Write several pages of back-story for your own use, to make sure your antagonist is as well-developed in your mind as your protagonist is, so that he/she radiates evil and power when you put them on the page. If you know your antagonist as well as you know the hero, the enemy will be believable when you write about their actions. The Hero’s Struggle: With the first calamity out of the way, the story is hurtling toward the midpoint, that place called the second plot-point. The characters are acting and reacting to events that are out of their control. Nothing is going right—the hero and his/her cohorts must scramble to stay alive, and now they are desperately searching for the right equipment or a crucial piece of information that will give them an edge. The struggle is the story, and at this point it looks like the hero may not get what they need in time. The adversary must first exploit the hero’s weaknesses. Only then can she overcome them and turn weakness into strength. The hero has a character arc and must grow into a stronger person. During this part of the story you must build upon your characters’ strengths. Identify the hero’s goals and clarify why he/she must struggle to achieve them.

Midway between the first plot point and the second plot point, what new incident will occur to once again dramatically alter the hero’s path? This will be a turning point, drama and mayhem will ensue, perhaps offering the hero a slim chance.

The books I loved to read the most were crafted in such a way that we got to know the characters, saw them in their safe environment, and bam! Calamity happened, thrusting them down the road to Naglimund or to the Misty Mountains. Calamity combined with villainy creates struggle, which creates opportunity for great adventure, and that is what great literature is all about. __________________________________________________________________________ Connie J. Jasperson is an author and blogger and can be found blogging regularly at Life in the Realm of Fantasy

1 Comment

Some of the best work I’ve ever read was in the form of extremely short stories. Authors grow in the craft and gain different perspectives when they write short stories and essays. With each short piece that you write, you increase your ability to tell a story with minimal exposition. This is especially true if you write the occasional drabble--a whole story in 100 words or less. These practice shorts serve several purposes: Writing such short fiction forces the author to develop economy of words. You have a finite number of words to tell what happened, so only the most crucial of information will fit within that space.

Writing a 100-word story takes less time than writing a 3,000-word story, but all writing is a time commitment. When writing a drabble, you can expect to spend an hour or more getting it to fit within the 100-word constraint. To write a drabble, we need the same basic components as we do for a longer story:

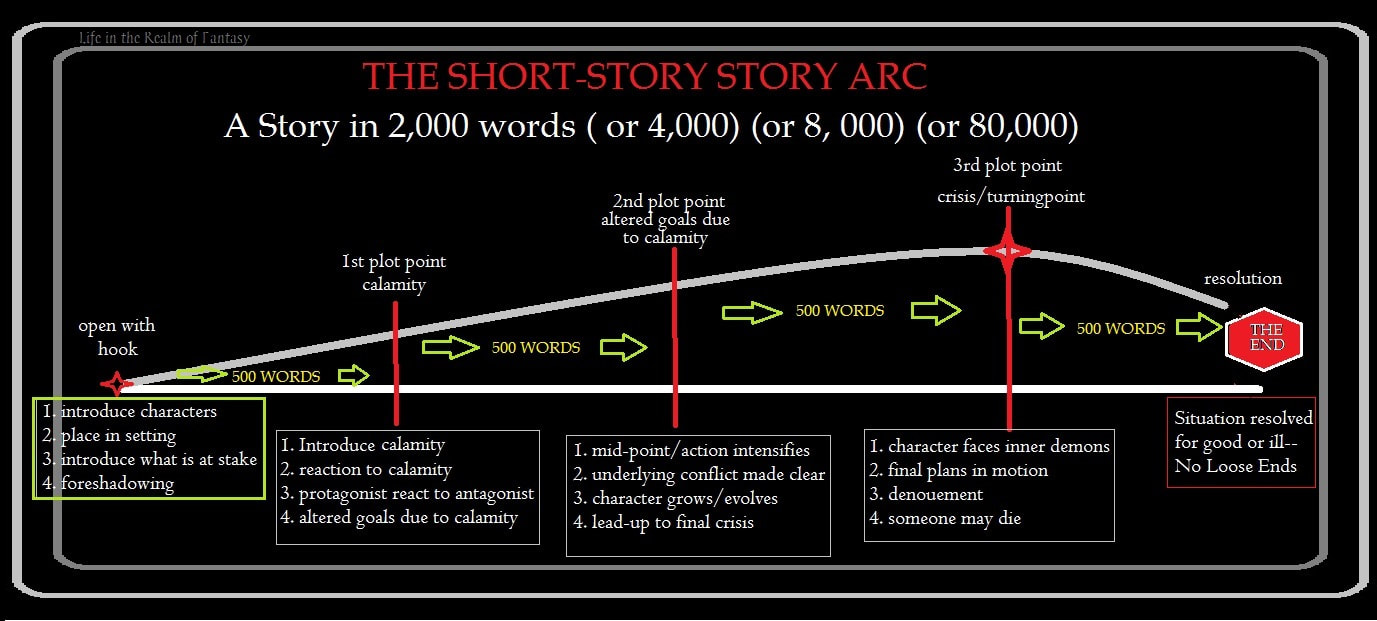

First, we need a prompt, a jumping off point. We have 100 words to write a scene that tells the entire story of a moment in the life of a character. Some contests give whole sentences for prompts, others offer one word, and still others no prompt at all. A prompt is a word or visual image that kick starts the story in your head. The prompt for the following story is sunset. We sat on the beach near the fire, two old people bundled against the cold Oregon sunset. Friends we’d never met fished the surf. Wind whipped my hair, gray and uncut, tore it from its inept braid. The August wind was chill inside my hood, but I remained, pleased to be with you, and pleased to be on that beach. Mist rose with the tide, closed in and enfolded us, blotting out the falling stars. Laughing at our folly, we dragged our weary selves back to our digs, rented, but with everything this old girl needed—love, laughter, and you. The above drabble is a 100-word romance, with a beginning, a middle, and an end. The beginning places our protagonist on the beach with someone for whom she cares deeply. The conflict in this tale? The mist and wind make it too cold for our protagonist to stay on the beach and gaze at the stars. A hard, cold wind and heavy mist are typical of the Washington and Oregon Coast in August, two things you wouldn’t think could coexist, but there, they do. The resolution? A cozy evening indoors. When I am writing a story to a specific word count limit, I break it into 4 acts. A drabble works the same way–we can break this down into its component parts and make the story arc work for us. We have about 25 words to open the story and set the scene, about 50 – 60 for the heart of the story, and 10 – 25 words to conclude it.

Drabbles are incredibly useful. They contain the ideas and thoughts that can easily become longer works. The above drabble, written in 2015, combined with a photograph I took while vacationing in Oregon with my husband in 2016, was the inspiration for what became a longer poem, Oregon Sunset. Good drabbles are the distilled essences of novels. They contain everything the reader needs to know about that moment and fills them with curiosity to learn what happened next. When you have a flash of brilliance, a shining moment of what if, write it in the form of a drabble. Save it in a file for later use as a springboard to write a longer work, or for submission to a drabble contest in its proto form. Spending an hour getting that idea and emotion down so you won’t forget it is a small gift you give yourself, as an author. Whether you choose to submit a drabble to a contest or hang on to it doesn’t matter. Either way, the act of writing a drabble hones your skills, and you will have captured the emotion and ambiance of the brilliant idea. That is what true writing is about. ____________________________________________________________________________________ Credits and Attributions: Writing the Extremely Short Story by Connie J. Jasperson was first published Jan 8, 2018 on Life in the Realm of Fantasy as How writing drabbles develops mad skills © 2018 by Connie J. Jasperson, All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission. The Short Story Arc Graphic by Connie J. Jasperson © 2015-2018. Used by permission. Connie J. Jasperson is an author and blogger and can be found blogging regularly at Life in the Realm of Fantasy. |

Archives

January 2023

Categories |

|

Contact us at:

Mailing Address: Northwest Independent Writers Association P.O. Box 1171 Redmond, OR 97756 Email: [email protected] [email protected] |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed